Michiganders now rely on telehealth for care. What’s next?

Virtual connections mean more access, especially for mental health needs, rural residents and ‘snowbirds’; new data could inform long-term policies now being developed

In just three years, millions of people across Michigan’s two huge peninsulas have taken advantage of their newfound ability to connect with their doctors, nurses and therapists through a computer or phone, a new report shows.

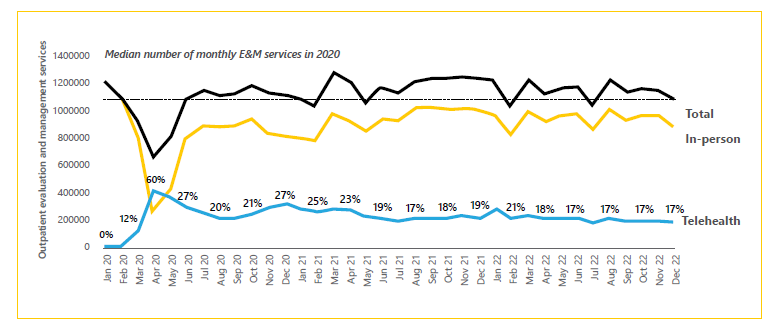

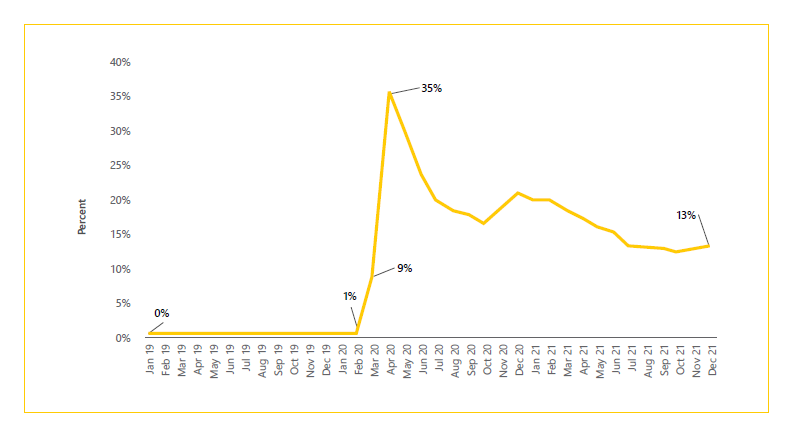

Between 11% and 17% of all appointments to evaluate symptoms or discuss treatment now take place virtually, depending on the type of insurance, the analysis shows.

That’s up from less than 1% of such visits before the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly spurred temporary flexibility in health insurance rules for telehealth, according to the report by a team from the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation.

The team used insurance data to prepare the report for the Michigan Health Endowment Fund and the Ethel and James Flinn Foundation.

Their analysis shows how telehealth has especially helped the 1 in 5 Michiganders who have mental health care needs – most notably those who live in the 38 counties that have few or no behavioral health care providers.

It also reveals lags in telehealth’s use by those living in rural areas, especially areas with lower percentages of homes with broadband Internet access. The team also examined telehealth across state lines, including by ‘snowbirds’ who split their time between Michigan and Florida.

Policy implications

Temporary telehealth rules will expire next year. So the report’s authors make recommendations they hope policymakers and private health insurance companies will note as they plan telehealth coverage for the long-term.

“From the Upper Peninsula to Detroit, and everywhere in between, it’s clear that Michiganders have embraced telehealth for the access and convenience it provides, as well as the original goal of reduced exposure to coronavirus,” said Chad Elllimoottil, M.D., M.S., the U-M researcher and telehealth expert who led the team. “But the future of telehealth in our state and beyond will depend on the decisions policymakers and insurance leaders make in coming months, not just for coverage but also for expansion of Internet access and the supply of mental health providers.”

Ellimoottil directs IHPI’s Telehealth Research Incubator and serves as medical director of Virtual Care for the University of Michigan Medical Group, part of U-M’s academic medical center called Michigan Medicine.

He worked on the report with researchers Ziwei Zhu, Xinwei Hi, Monica Van Til, who together analyzed data on traditional fee-for-service Medicare and some data from patients covered by private managed care plans from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, as well as with Sarah Clark who analyzed Medicaid data.

On August 10, Ellimoottil will speak about the findings and more at a webinar hosted by the Michigan Health Endowment Fund; information and a link for registration are here.

“This report highlights how telehealth has transformed the way we think about access to care across Michigan, including dramatic shifts in the delivery of behavioral health care,” said Becky Cienki, director of Behavioral Health and Special Projects at the Michigan Health Endowment Fund. “We're excited for the valuable insights revealed in the data and the ways they will equip providers and policymakers to make informed, effective decisions that maximize the benefits of telehealth to expand access to care.”

Key findings:

Telehealth visits by insurance source:

In all, 11% of visits by Medicare participants were done via telehealth in 2022, compared with 13% of Medicaid-covered visits and 17% of visits billed to private insurance. In addition, 10% of people with Medicare coverage who sought care at ‘safety net’ clinics were seen via telehealth.

The overall volume of outpatient visits by people covered by both traditional Medicare and private insurance remained steady from mid-2020 through the end of 2022, so Ellimoottil notes that this indicates telehealth substituted for appointments that would otherwise have been in person, rather than adding to the number of visits.

Rural vs. non-rural:

Before the pandemic, Medicare and other insurers had narrow requirements for telehealth, focused on people living in rural areas. But they could only get coverage for such visits if they left home and went to a local clinic to sign on.

The new study finds that in 2019, rural counties in central and northern Michigan had the highest rates of telehealth visits per 1,000 residents. But by 2020 and 2021, the counties with the highest rates of telehealth use were also the most populated counties, especially the five counties of southeast Michigan where nearly half of the state’s population lives.

In all, about 31% of people living in rural counties had a telehealth visit, compared with 46% of those in non-rural counties. The authors note that continued coverage of telehealth from home, rather than reverting to access only from rural clinics, will be important.

Mental and behavioral health:

Telehealth has long been seen as a potential option for delivering care for mental health conditions and substance use disorders including drug and alcohol addiction, because it often doesn’t require a “hands on” approach. Plus, patients often feel a stigma against seeking treatment in person, and there is both a shortage and uneven distribution of providers trained to care for patients with these conditions.

Telehealth use: The new report includes an analysis that confirms previous estimates that 1 in 5 people in Michigan have a mental health or behavioral health condition at any given time. Past studies have suggested that 40% of all adults with mental health conditions, and 80% of those with addiction issues, do not receive care.

The report shows that almost half of all visits for mental/behavioral health care now happen by telehealth among Michiganders covered by traditional Medicare, based on two different analyses.

They also determined which counties have patients receiving the most mental and behavioral health care. For people with Medicaid coverage living in these high-demand counties, the percentage having mental and behavioral health care visits by telehealth was much lower than it was for Medicare, at about 17% of such visits.

Provider shortage: The report also shows that half of all Michigan counties have less than 10 mental health specialists, defined as practicing specialists in psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, neuropsychiatry, psychology, clinical psychology, licensed clinical social work, or addiction medicine. One in 5 Michigan counties have one or no such providers.

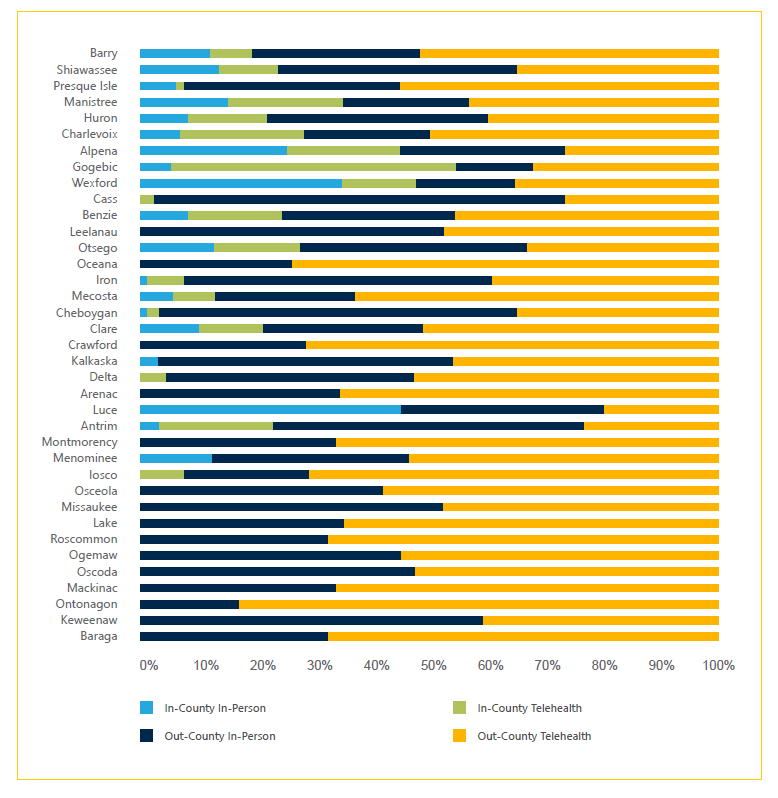

The team focused on 38 counties with the most dire shortages. In those counties, 57% of all visits with such providers took part via telehealth, for patients with traditional Medicare.

Getting help outside shortage counties: The researchers drilled further to look at the locations where patients lived compared with the location where their mental/behavioral health provider practiced, to see if the availability of telehealth was making it easier to get care from providers based in areas with a higher supply of providers.

In all, 82% of mental health visits by people living in counties with mental health provider shortages involved providers outside the patient’s home county. Of those, the majority were conducted via telehealth – in fact, out-of-county telehealth made up 47% of all mental health visits for people living in these shortage counties.

In 13 counties, all mental/behavioral health visits by county residents were with providers in a different county.

These data show that telehealth meant greater access to mental health care for people living in areas that lack providers of such care.

Broadband Internet access:

The higher the percentage of households that have broadband Internet access in a county, the higher the use of telehealth by Medicare participants there.

The authors note that efforts to increase broadband availability statewide, but especially in the 29 counties that fall below the median level of broadband availability (82% of households), could increase the use of telehealth.

Demographics:

The researchers saw minimal differences in telehealth use along lines of age, gender, race/ethnicity, though women and people under age 65 were slightly more likely to use telehealth. Interestingly, they did see a higher rate of telehealth use among people who are eligible for both Medicaid because of low income and Medicare because of age or disability status; this “dual-eligible” population accounted for 23% of all telehealth users covered by traditional Medicare in 2020.

While the new report did not look at what percentage of telehealth visits were done through a telephone voice connection only, previous research by U-M teams suggests that discontinuation of insurance coverage for phone visits may reduce telehealth access for patients who are older, African-American, need an interpreter, rely on Medicaid, and/or live in areas with limited broadband access.

Snowbirds and other out-of-state telehealth:

The temporary pandemic rules that allowed patients to see providers who are located in a different state led to more appointments of this kind in Michigan. But the percentage of all telehealth visits by Michiganders with Medicare that involved out-of-state providers stayed the same at about 3%.

More than a quarter (28%) of all visits by Michiganders who saw a provider in another state virtually involved providers in Florida. These are likely Michigan “snowbirds” who spend part of their year in Florida and may have appointments with their providers there even when they’re back in Michigan.

Most of the other visits with out-of-state providers involved providers in states that neighbor Michigan. Ellimoottil says this suggests that policymakers should prioritize medical licensing reciprocity agreements with neighboring states and Florida, to give patients continued access to this kind of care.

More information:

Learn more about telehealth research and policy work at IHPI: https://ihpi.umich.edu/telehealth-research-and-policy

Learn more about the Michigan Health Endowment Fund’s telehealth work: https://mihealthfund.org/issues/telehealth

In addition to the report team, the analysis involved members of the Susan B. Meister Child Health Evaluation and Research (CHEAR) Center who worked on the Medicaid analysis, and data from the Michigan Value Collaborative which provided access to data from BCBSM Preferred Provider Organization Commercial insurance claims data from 103 acute care hospitals and 40 physician organizations across Michigan.

.