This brief examines approaches that states are taking to restrict access to short-term health plans, which offer limited benefits and do not cover maternity care.

April 2019

Maternity Coverage is Important for Healthy Moms and Babies

Insurance coverage helps expecting moms access maternity care services that are proven to reduce preterm birth, delivery complications and infant mortality. [1]

Coverage helps moms manage serious medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and substance use disorder. These conditions affect at least 10% of pregnancies (with higher rates in rural and low-income communities) and put women at increased risk of pregnancy complications. [2]

Half of pregnancies in the U.S. are unplanned, and nearly 4 million babies are born every year in the U.S.

The Evolving Policy Landscape Affecting Maternity Coverage

Many women—even those with health insurance—lacked maternity coverage prior to 2014.

- Overall, 6 in 10 pregnant women had coverage gaps during 2005 to 2013. [3]

- Only 12% of individual health insurance plans included maternity coverage. [4]

- Women without maternity coverage faced significant costs for care (typical price charged for pregnancy and newborn care: $32,000 for an uncomplicated vaginal birth; $51,000 for an uncomplicated cesarean birth). [5]

In 2014, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) increased access to maternity services by:

- Requiring individual plans to cover maternity services as an “essential health benefit."

- Limiting access to short-term plans by restricting their duration and renewability.

Federal regulations that went into effect in October 2018 re-expanded access to short-term plans by:

- Extending their duration to 12 months (up from 3 months).

- Allowing insurers to renew coverage for up to 36 months.

What are short-term plans?

Short-term plans were designed to provide coverage for major medical events for a limited duration of time. They are not required to cover essential health benefits or comply with other ACA market reforms. None cover maternity services, according to one review of short-term plans offered in 45 states and the District of Columbia on two online private insurance marketplaces (eHealth and Agile Health Insurance).

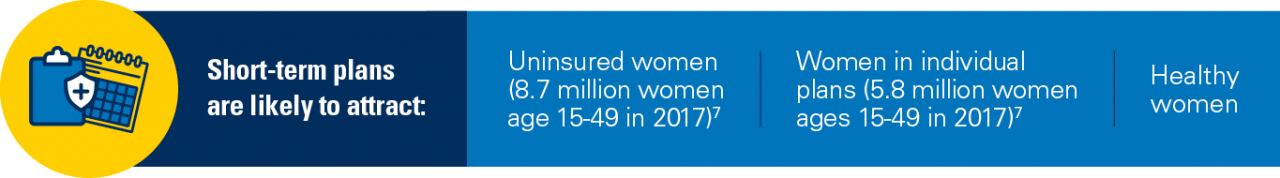

Expanded Access to Short-Term Plans May Mean More Women Without Maternity Coverage

Since pregnancy is not a planned healthcare event for many women, they may not consider the importance of maternity coverage when shopping for insurance.

Pregnancy itself is not considered a qualifying life event and does not make a woman eligible for a Special Enrollment Period. If a woman covered by a short-term plan becomes pregnant outside of the open enrollment period, she may face significant out-of-pocket spending for maternity care.

Short-Term Plans May Be Attractive to Some, But May Have Health and Financial Consequences for Mother and Child

Why might short-term plans be attractive to women?

- Lower premiums than marketplace plans (due to limited benefits and preexisting condition exclusions).

- No enrollment periods (coverage can start immediately).

- Act as a bridge during insurance gaps, providing some coverage in case of major medical events.

How might short-term plans harm women?

- Limited benefits (no coverage for maternity care; limited or no coverage for preventive care, prescriptions, behavioral healthcare).

- High out-of-pocket spending for routine healthcare

- Won’t help with really costly services (most plans cap annual coverage at $2 million or less). [7]

- Can deny coverage or charge more based on individual characteristics (such as gender, age, and pre-existing conditions—including pregnancy).

- Plan renewability isn’t guaranteed (often can’t keep the plan if you get sick).

- Healthy people may leave state-run marketplaces, resulting in higher premiums for those remaining.

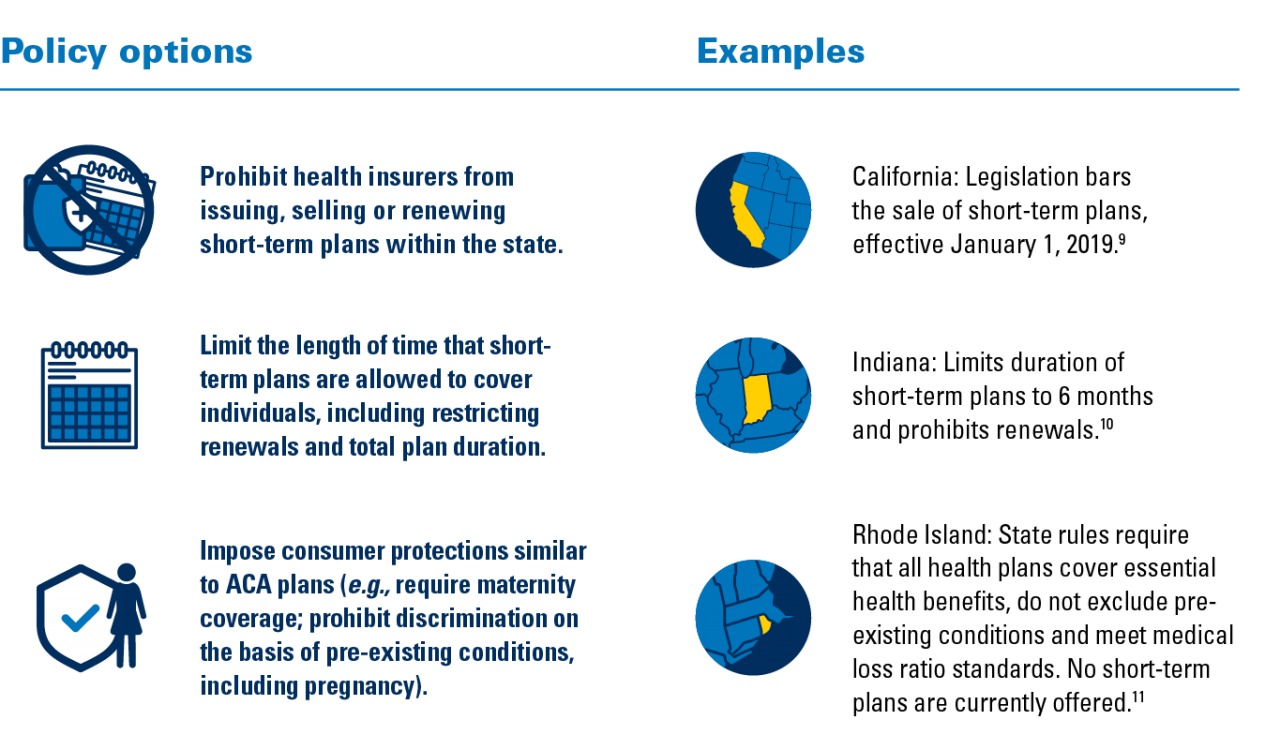

State Regulatory Options to Support the Health of Moms and Babies

States have regulatory authority over short-term plans and have various policy options to address women’s access to maternity coverage and care that improves maternal-child health. [8] The chart below outlines some of the approaches that states have taken.

Resources

1. Health insurance is a family matter. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance (2002).The National Academies Press. PMID: 25057625 doi:10.17226/10503

2. Disparities in chronic conditions among women hospitalized for delivery in the United States, 2005-2014. Admon, L., Winkelman, T., Moniz, M., Davis, M., Heisler, M., Dalton V. (2017). Obstet Gynecol. PMID: 29112666 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002357

3. Women in the United States experience high rates of coverage ‘churn’ in months before and after childbirth. Daw, J., Hatfield, L., Swartz, K., Sommers, B. (2017). Health Affairs. PMID: 28373324 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1241

4. Turning to fairness: Insurance discrimination against women today and the Affordable Care Act. National Women’s Law Center (2012). www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/nwlc_2012_ turningtofairness_report.pdf

5. The cost of having a baby in the United States. Truven Health Analytics Marketscan Study (January 2013). http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Cost-of-Having-a-Baby1.pdf

6. Understanding short-term limited duration health insurance. Pollitz, K., Long, M., Semanskee, A., Kamal, R. (2018). Kaiser Family Foundation. www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/understanding-short-term-limited-duration-health-insurance/

7. State health facts: Health insurance coverage of women ages 15-49. Kaiser Family Foundation (2017). https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/health-insurance-coverage-of-women-ages-15-49/

8. Short-term, limited-duration insurance. 45 C.F.R. § 144, 146, 148.08. (2018). https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection. federalregister.gov/2018-16568.pdf

9. Short-term limited duration health insurance, CA-S.B. 910. (2018). http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billStatusClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB910

10. Indiana Department of Insurance. Bulletin 244 (2018). www.in.gov/idoi/files/Bulletin%20244.pdf

11. State of Rhode Island Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner, Health Insurance Advisory Council (2018). www.ohic.ri.gov/ documents/HIAC%20docs/2018-2019/09.25.2018-HIAC-minutes-amended.pdf

AUTHORS

Michelle Moniz, MD, MSc, FACOG

Marisa Wetmore, MPP

Katie Allan, BA

CONTRIBUTORS

Vanessa Dalton, MD, MPH, FACOG

A. Mark Fendrick, MD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This policy brief was supported by the IHPI Policy Sprint program, which provides funding and staff assistance to IHPI member-led teams in undertaking rapid analyses to address important health policy questions and develop products that inform decision-making at the local, state, or national level.