Women with inflammatory breast cancer are living longer, but the gap between white and black patients persists

A U-M Rogel Cancer study provides an updated, more comprehensive look at trends for this rare, aggressive form of breast cancer over the last four decades.

Women with inflammatory breast cancer — a rare, highly aggressive form of the disease — are living about twice as long after diagnosis than their counterparts in the mid-to-late 1970s, according to a new University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center study.

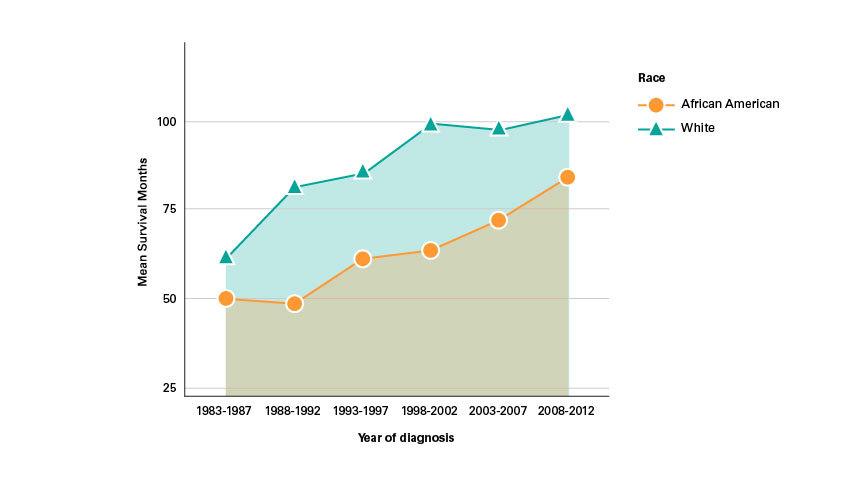

The researchers found that from 1973-1977, patients diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer, also known as IBC, survived for an average of about 50 months, compared to 100 months for patients diagnosed from 2008-2012.

But despite overall improvements in survival, the analysis showed an ongoing disparity between white patients and Black patients. And while the gap has narrowed slightly over time, white patients today still tend to live about two years longer than their Black peers, the group found.

The incidence of IBC among Black women is also more than 70% higher than in white women, affecting 4.5 Black women out of 100,000 compared to 2.6 white women, according to the study, which was published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

“Our findings make it clear that more research is needed to understand factors behind these racial disparities,” says study first author Hannah Abraham, a graduate student in the U-M Cancer Biology program. “These factors might include awareness about the signs and symptoms of IBC among Black patients, biological and genetic differences, delays in diagnosis and treatment, the standard of care patients receive, including follow-up and survivorship care, and environmental factors.”

What makes IBC different

Inflammatory breast cancer accounts for only a tiny fraction of breast cancers, so its symptoms are less well known and the disease has received less attention from researchers. It also has different physical signs than other types of breast cancer; instead of a lump, IBC causes swelling and visible changes in the skin around the breast — including redness and a dimpling of the skin called peau d'orange, which is French for the skin of an orange.

IBC also tends to show up in women at a younger age and spread more quickly than other types of cancer. And because the cancer cells have already grown into the skin by the time symptoms appear, it’s typically diagnosed at stage 3 or stage 4.

Unlike strides made against other types of breast cancer, there aren’t yet any targeted therapies against IBC.

Data paints a more complete picture

The U-M study analyzed data from the National Cancer Institute’s authoritative cancer registries — known as Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results, or SEER. The analysis was unique in including not only patients who had a diagnosis of IBC based on pathology reports, but also those with clinical symptoms consistent with IBC — bringing the number of patients included in the study to nearly 30,000.

The team included two epidemiologists from the U-M School of Public Health: Yaoxuan Xia and Bhramar Mukherjee, Ph.D., chair of the department of biostatistics and a member of the Rogel Cancer Center.

“We found that in these additional patients, the incidence rates by race were consistent with previously reported trends. This gave us confidence that our method was uncovering additional cases that had gone underreported in the past or were possibly misclassified in previous analyses,” says study senior author Sofia Merajver, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk and Evaluation Program at the Rogel Cancer Center. “So therefore we believe our study is able to offer the most comprehensive assessment of incidence and survival rates of IBC to date.”

Research finds although patients diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer are living longer, disparities persist. Image by Stephanie King

Several factors are responsible for the big jump in survival time for IBC over the last four decades, Abraham notes. These include a broader awareness of

Several factors are responsible for the big jump in survival time for IBC over the last four decades, Abraham notes. These include a broader awareness of the disease and improved consensus about the most effective ways to treat it with a combination of chemotherapy first, then surgery and radiation.

“This is a rare, orphan disease,” Merajver adds. “We owe a lot to the long-term survivors and tireless advocates who have raised awareness about IBC within the general public as well as the medical community.”

Tireless advocates

One of those advocates is Terry Arnold, founder of the IBC Network Foundation, who was diagnosed with the disease in 2007.

“Thirteen years ago, there wasn’t any information about inflammatory breast cancer on the websites of many of the biggest breast cancer advocacy groups — the household names,” Arnold says. “We had to lobby to get that changed.”

Even today, Arnold says women frequently share stories with her of doctors whose lack of knowledge about IBC leads them to treat it the same as other types of breast cancer, leading to poorer outcomes for the patients.

“There is definitely not enough education about IBC within the medical community,” she says. “And unfortunately, the ones that don’t make it are the ones whose voices we lose in raising awareness.”

Due to the disease’s poor prognosis, many doctors recommend that patients not research it on the internet, Arnold adds. However, due to IBC’s rarity, trusted sites like the National Cancer Institute and IBC groups like hers can help patients inform themselves in order to better advocate for their own care, she says.

The U-M study was funded in party by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the National Cancer Institute’s core grant to the Rogel Cancer Center (P30CA046592).

Paper cited: “Incidence and Survival of Inflammatory Breast Cancer between 1973 – 2015 in the SEER Database,” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. DOI: 10.1007/s10549-020-05938-2