Opioid prescribing limits for acute pain have had modest effects in limiting overprescribing. Researchers outline why that may be and discuss potential policy considerations to maximize the ability of limits to reduce excessive prescribing.

Opioid Prescribing Limits for Acute Pain

The opioid epidemic has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in the U.S. over the past decade.1 Opioids are commonly prescribed for acute pain, but the amount in prescriptions often greatly exceeds what patients need.2 Leftover opioids can be diverted or misused, adding fuel to the epidemic.

Definition: acute pain is the sudden onset of pain that lasts no longer than 90 days, such as pain after surgery.

To reduce leftover opioids, at least 35 states have implemented limits that restrict either the duration or number of doses in opioid prescriptions for acute pain (as of October 2019). Limits have also been implemented by many health insurers, at least one major pharmacy chain, and the three largest pharmacy benefit managers in the country, which collectively manage drug benefits for 180 million Americans.3 Consequently, almost every opioid prescription for acute pain in the U.S. is now subject to at least one limit.

Unfortunately, early evidence suggests that the effects of limits on opioid prescribing have been modest at best.4-8 For example, one study found that implementation of 26 state limits was associated with just a 7% decrease in the duration of opioid prescriptions for patients new to opioid therapy.7

To identify potential explanations for these modest effects, a University of Michigan research team assessed variation in the design of state opioid prescribing limits.

Variation in the design of state opioid prescribing limits

Thirty states with comprehensive state limits (i.e., not limited to opioid prescriptions from specific settings, such as emergency departments) were included in the analysis. The analysis was completed in October 2019.

The team found that limits vary along many dimensions:

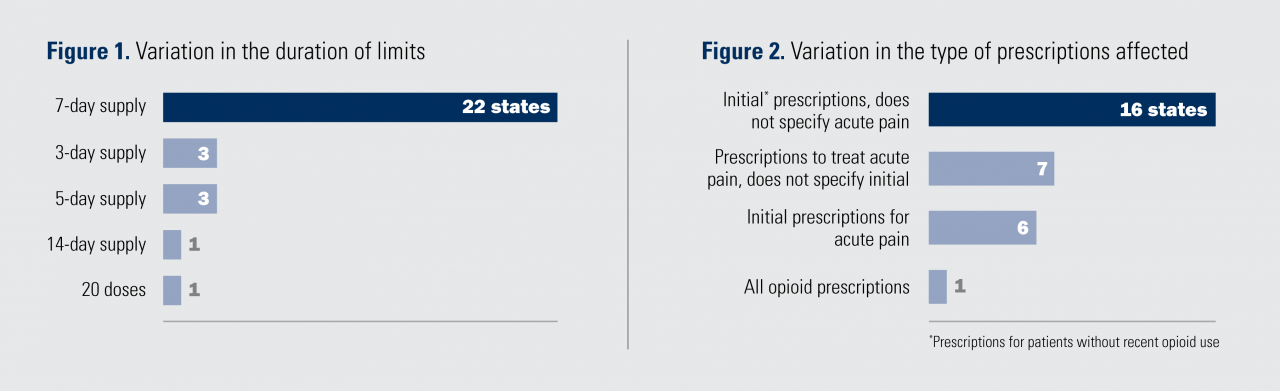

- Duration: Most limits restrict prescriptions to a 7-day supply, but some allow for a 14-day supply while others allow for a 3-day supply (Figure 1). Eight states also have a limit of daily or total dosage.

- Prescriptions Affected: Some limits affect prescriptions for “acute pain”, while others affect “initial prescriptions” for opioid-naïve patients. Some limits only affect prescriptions for opioids with high potential for misuse (e.g., “Schedule II” opioids) (Figure 2).

- Exceptions: Some state limits have no exclusions, while others have many. Common exclusions include: end-of-life care (25 states), cancer (25 states), chronic pain (17 states), and substance use disorder treatment (15 states). Some states have exceptions for a clinician’s “professional judgement” (12 states).

What might account for the modest effects of limits on opioid prescribing?

Limits are too high: For a limit to reduce prescribing, it must restrict prescribing to a level that is lower than what the clinician would have otherwise written.

- In a national study of privately insured patients, the average duration of initial opioid prescriptions at the end of 2017 was approximately a five-day supply.9 However, most state limits set a seven-day supply restriction (Figure 1), meaning that most opioid prescriptions are not affected.

Limits are imprecisely designed: Most limits restrict the duration (days supplied) of prescriptions, but few concurrently restrict daily dosage.10 This may allow clinicians to still prescribe the same amount they would have previously.

- For example, under a new seven-day supply limit with no daily dosage restriction, clinicians who normally prescribe 84 pills over a 14-day period by writing for one pill every four hours could instead prescribe 84 pills over a seven-day period by writing for two pills every four hours.

Limits are sometimes voluntary: Allowing exceptions for professional judgment preserves clinician autonomy but may make limits more like guidelines than mandates.

Clinicians may not comply:

- Clinicians may not understand whether a limit should be applied due to lack of clarity.

- For example, state limits that restrict initial opioid prescriptions often do not define how long a patient must have been opioid-free for the prescription to be considered “initial”.

- Clinicians may not understand which rules to follow when there are conflicts between the limits of states, insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, and pharmacies.

- Clinicians may choose not to comply with limits if enforcement is inconsistent or when patients have extenuating circumstances.

- Clinicians may engage in “gaming” behavior.

- To provide patients with a larger opioid supply than allowed, they could write multiple short-duration prescriptions. For example, to provide a 14-day supply under a seven-day supply limit, the clinician could provide two paper prescriptions, each with a seven-day supply, writing in a future date for the second prescription.11

Could making limits more restrictive make them more effective?

If every patient needed only a three-day supply of opioids, a uniform three-day supply limit could eliminate all excessive prescribing without worsening patient pain control.

However, pain needs vary widely within conditions and between conditions,12-13 making it impossible for any limit to achieve this ideal.

A highly restrictive limit will reduce prescribing to a greater degree than a less restrictive limit, but will also increase the number of patients who experience worsened pain control.

What are the implications for policy?

To maximize the ability of limits to reduce excessive prescribing and minimize the potential for worsened pain control, policymakers could consider the following options.

- Restrict patients’ initial opioid prescriptions rather than prescriptions for acute pain. It is not always clear what constitutes acute pain, and pharmacists may not know whether prescriptions were written for acute versus chronic pain. Limits that target initial prescriptions may be easier to implement given the widespread availability of prescription drug monitoring program databases.

- Implement precise limits that restrict both duration and daily dosage.

- Clearly indicate which prescriptions are affected (e.g., explicitly define “initial” opioid prescriptions).

- Require electronic prescribing to prevent clinicians from gaming limits by post-dating paper opioid prescriptions.

- Coordinate limits among states, insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, and pharmacies to prevent confusion.

- Support the development and dissemination of evidence-based, condition-specific opioid prescribing recommendations.

- Recommendations are based on patient-reported opioid consumption data and reflect average patient pain control needs for a condition.

- The Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network has developed procedure-specific recommendations.14 Evidence suggests that these recommendations can substantially reduce opioid prescribing without worsening pain control or increasing the need for refills of opioid prescriptions.15

OUR PUBLISHED RESEARCH

Disappointing Early Results From Opioid Prescribing Limits for Acute Pain. Chua KP, Kimmel L, Brummett CM. JAMA Surg. 2020 Mar 11. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.58591.

Association of State Opioid Duration Limits With Postoperative Opioid Prescribing. Agarwal S, Bryan JD, Hu HM, Lee JS, Chua KP, et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Dec 2;2(12):e1918361. PMID: 31880801. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18361.

Opioid Prescribing Limits for Acute Pain: Potential Problems With Design and Implementation. Chua KP, Brummett CM, Waljee JF. JAMA. 2019 Jan 31;321(7):643-644. PMID: 30703214. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0010.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

1 Overdose Death Rates. National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2020. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdosedeath-rates. Accessed April 8, 2020.

2 Prescription Opioid Analgesics Commonly Unused After Surgery: A Systematic Review. Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. JAMA Surgery. 2017 Nov 1;152(11):1066-1071. PMID: 28768328. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831.

3 Health Policy Brief: Pharmacy Benefit Managers. Werble C. Health Affairs. 2017. doi:10.1377/hpb20171409.000178.

4 Impact of State Laws Restricting Opioid Duration on Characteristics of New Opioid Prescriptions. Dave CV, Patorno E, Franklin JM, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2339-2341. PMID: 31309407. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05150-z.

5 Association of State Opioid Duration Limits with Postoperative Opioid Prescribing. Agarwal S, Bryan JD, Hu HM, et al. JAMA Network Open. 2019 Dec 2;2(12):e1918361. PMID: 31880801. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18361.

6 Opioid Prescribing Laws are not Associated with Short-term Declines in Prescription Opioid Distribution. Davis CS, Piper BJ, Gertner AK, Rotter JS. Pain Med. 2019;21(3):532-537. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz159.

7 Can Policy Affect Initiation of Addictive Substance Use? Evidence From Opioid Prescribing. Sacks DW, Hollingsworth A, Nguyen TD, Simon KI. NBER Working Paper No. 25974. 2019. https://www.nber.org/papers/w25974.

8 Impact of a State Opioid Prescribing Limit and Electronic Medical Record Alert on Opioid Prescriptions: A Difference-in-Differences Analysis. Lowenstein M, Hossain E, Yang W, et al. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Oct 10. PMID: 31602561. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05302-1.

9 Initial Opioid Prescriptions Among U.S. Commercially Insured Patients, 2012-2017. Zhu W, Chernew ME, Sherry TB, Maestas N. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(11):1043-1052. PMID: 30865798. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1807069.

10 Laws Limiting the Prescribing or Dispensing of Opioids for Acute Pain in the United States: A National Systematic Legal Review. Davis CS, Lieberman AJ, Hernandez-Delgado H, Suba C. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Jan 1;194:166-172. PMID: 30445274. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.022.

11 Opioid Laws Hit Physicians, Patients in Unintended Ways. Greene J. 2018. http://www.crainsdetroit.com/article/20180729/news/667241/opioid-laws-hit-physicians-patients-in-unintended-ways. Accessed April 8, 2020.

12 Association of Opioid Prescribing with Opioid Consumption After Surgery in Michigan. Howard R, Fry B, Gunaseelan V, et al. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(4):e184234. PMID: 30422239. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4234.

13 Limiting the Duration of Opioid Prescriptions: Balancing Excessive Prescribing and the Effective Treatment of Pain. Bateman BT, Choudhry NK. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 May 1;176(5):583-584. PMID: 27043188. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0544.

14 Opioid Prescribing Recommendations for Surgery. Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network. 2019. https://opioidprescribing.info. Accessed April 8, 2020.

15 Statewide Implementation of Postoperative Opioid Prescribing Guidelines. Vu JV, Howard RA, Gunaseelan V, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(7):680-682. PMID: 31412184. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1905045.

RELATED IHPI NEWS ARTICLES

Impact of opioid prescribing limits is modest at best, early evidence shows

AUTHORS

Kao-Ping Chua, M.D., Ph.D., and Lauren Kimmel, B.S.

Susan B. Meister Child Health Evaluation and Research Center

Department of Pediatrics

University of Michigan Medical School

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This policy brief was supported by the IHPI Policy Sprint program, which provides funding and staff assistance to IHPI member-led teams in undertaking rapid analyses to address important health policy questions and develop products that inform decision-making at the local, state, or national level.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Please contact Eileen Kostanecki, IHPI’s Director of Policy Engagement & External Relations, at [email protected].