A research team at the University of Michigan studied whether hospital system participation in the 340B drug pricing program was associated with initiation of oral specialty drugs and adherence to treatment among men with advanced prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men in the United States and the second leading cause of cancer death, accounting for nearly 35,000 deaths each year.1

Treatment options for men with advanced prostate cancer have evolved in recent years, expanding from chemotherapy to oral specialty drugs (i.e, abiraterone, enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide), which target specific molecules affecting tumor growth.2–4 They are more convenient for patients, have fewer side effects than chemotherapy, and have demonstrated improvements in overall survival. The development of these drugs has changed the standard of care for patients with advanced prostate cancer in recent years, and the therapies are being prescribed more often and by a greater number of providers.5–6

Oral specialty drugs for advanced prostate cancer, however, are substantially more expensive than traditional therapies.7 Given the high cost of these oral specialty drugs, men who are socially and economically vulnerable may have particular difficulties accessing, initiating, and adhering to treatment. Such men are also more often diagnosed with the advanced form of prostate cancer and may therefore stand to especially benefit from these oral specialty drugs.8 However, high out-of-pocket costs for healthcare as well as health-related social needs such as housing instability, job insecurity, lack of transportation, food insecurity, lower educational attainment, and multiple health problems can contribute to a lack of initiation and adherence to treatment.

Numerous public and private programs and policies have been created to support patients and the healthcare entities that care for them, particularly for vulnerable populations. One such example is the federal 340B Drug Pricing Program. Participating healthcare entities in the 340B program include hospitals and other healthcare organizations that serve a disproportionate number of Medicaid and low-income Medicare patients. The program is intended to enable participating entities to stretch scarce resources, reach more patients, and provide more comprehensive services by requiring pharmaceutical manufacturers to provide discounts on select outpatient medications purchased by the participating entities.9–10

Prior studies have looked at the effect of the 340B program on patient care and found mixed results.11–14 On a more granular level, studies have not looked at whether hospital participation in the 340B program is associated with prescription drug use for advanced prostate cancer.

To further explore this topic, a research team at the University of Michigan studied whether hospital system participation in the 340B program was associated with initiation of oral specialty drugs and adherence to treatment among men with advanced prostate cancer. The team was especially interested in understanding the effects for patients living in communities with economic, housing, transportation, and other challenges, as measured by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI).

Takeaways from the research

Using national Medicare Part D claims data, the team studied initiation of the oral specialty drugs abiraterone, enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide among men with advanced prostate cancer and their adherence to treatment in the first six months. The men in the dataset were diagnosed with and treated for advanced prostate cancer at a hospital system between 2012 and 2019.

The team then assessed whether a patient received care at a 340B-participating hospital system or a non-340B participating hospital system, and the social vulnerability index of their community (based on the zip code of their residence).

Initiation of oral specialty drugs for advanced prostate cancer

Men initiated treatment at the same rates whether they received care at a 340B-participating or non-340B participating hospital system (22% vs 23%). However, when looking at social and economic vulnerability, men from the most vulnerable communities were less likely to start treatment:

Adherence rates in the first six months after starting treatment

Men who were taking oral specialty drugs had similar overall adherence rates whether or not the hospital system participated in the 340B program (69% adhered to treatment).

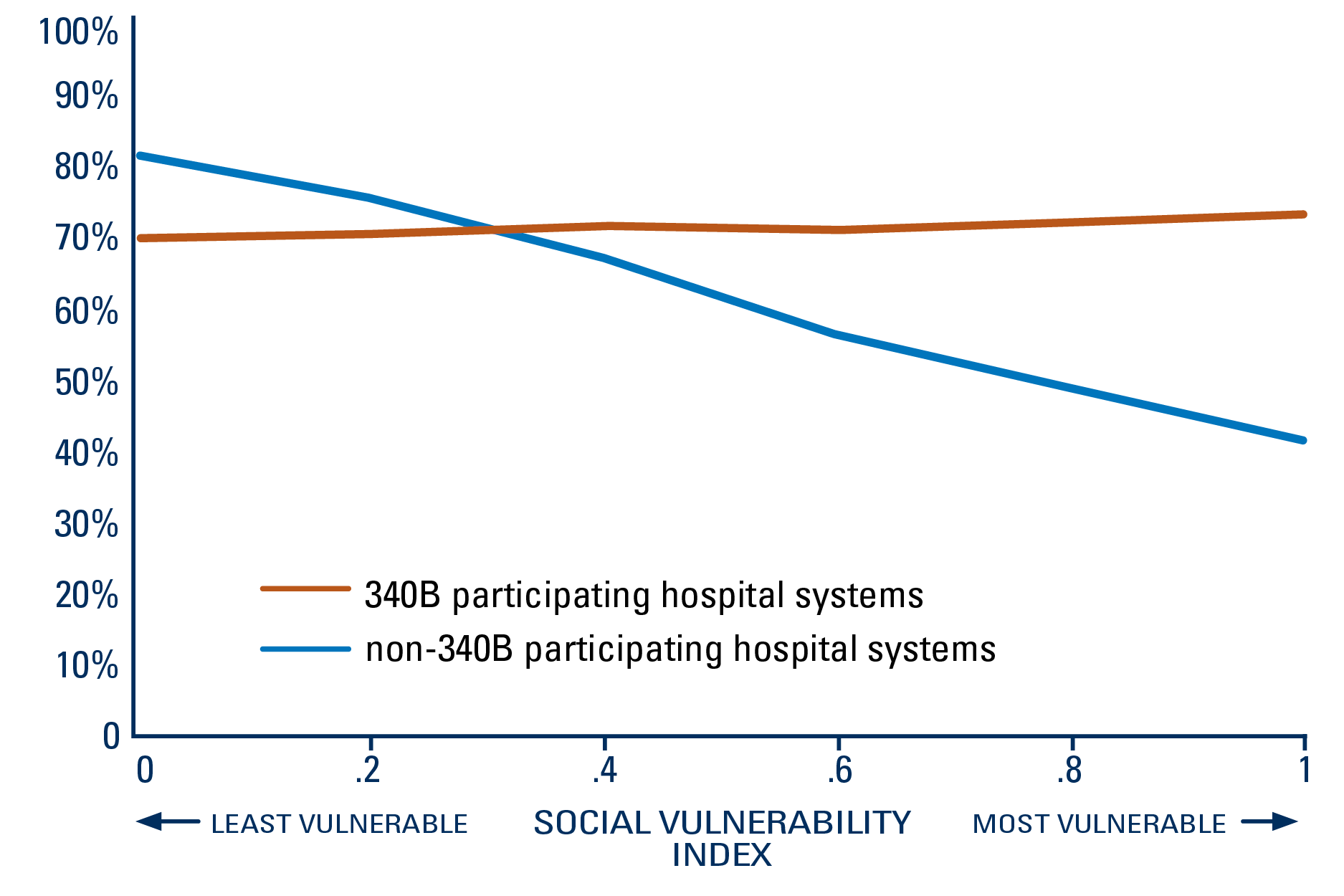

When looking at social and economic vulnerability, there was a decline in adherence rates among those cared for at a non-340B participating hospital system as the vulnerability level of the community increased. However, men in the most vulnerable communities were more likely to continue treatment if cared for at a 340B-participating hospital system than a non-participating hospital system (71% vs. 42%).

340B was associated with higher adherence to oral specialty medications among men with advanced prostate cancer from more socially vulnerable communities

PERCENT OF PATIENTS WHO ADHERED TO TREATMENT IN THE FIRST SIX MONTHS, BY SOCIAL VULNERABILITY LEVEL OF THEIR COMMUNITY

Referenced study: The 340B Program and Oral Specialty Drugs for Advanced Prostate Cancer. Faraj KS, Kaufman SR, Oerline M, et al. Cancer. 2024. doi:10.1001/cncr.35262.

Methods: Defining initiation of therapy: The team used Medicare Part D claims to identify the first time an oral specialty drug prescription was filled by a patient. Defining adherence to treatment: The team assessed adherence by looking at the proportion of days covered, which was calculated by summing the number of days of supply for a prescription divided by the time period of interest. A patient was considered as adhering to treatment if at least 80% of the days were covered. This measure was assessed only for men who had follow-up for at least 6 months after treatment initiation.

What are the implications for health policy and practice?

This study shows that overall, men across the country with advanced prostate cancer initiated oral specialty medications and adhered to treatment at the same rates whether or not the hospital system they received care from participated in the 340B drug pricing program.

It is important to note that there had been a paradigm shift in the management of advanced prostate cancer throughout the study period, with providers prescribing the drugs with increasing frequency and for earlier stages of the disease toward the end of the study period. However, specialty drug use by eligible patients has been underutilized,5 despite established survival benefits15–16 and national guideline recommendations.17 While there are many reasons for underutilization, socioeconomic factors can play a significant role.

When taking social and economic vulnerability of the community into account, the team found that men from more vulnerable areas were less likely to start treatment with specialty drugs. However, men from the most vulnerable communities receiving care at 340B-participating hospital systems had significantly higher adherence rates than at non-340B participating hospital systems.

The reasons behind the higher adherence rates are unclear, as the team did not assess patient and provider attitudes and beliefs toward treatments nor strategies or programs that hospital systems used that may have impacted adherence rates. Further investigation into these factors could help identify strategies and programs that might improve patient outcomes that could be replicated by other health care entities.

The team noted that referrals by hospital systems to cost assistance programs, medication delivery services, or programs involving support from additional healthcare professionals, such as pharmacists, to provide patients with education and tools to manage their disease, have been known to help patients access healthcare treatment and remain on treatment. Additionally, to help patients navigate complex needs and improve care and health outcomes for men with advanced prostate cancer, providers and health care entities could consider developing screening tools and processes to identify patients at risk for disparities (i.e., those less likely to start and remain on treatment).

References

1. Key Statistics for Prostate Cancer. American Cancer Society. Accessed May 31, 2023. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html.

2. Abiraterone in Metastatic Prostate Cancer without Previous Chemotherapy. Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. N Engl J Med. Jan 10 2013;368(2):138–48. PMID:23228172. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209096.

3. Increased Survival with Enzalutamide in Prostate Cancer after Chemotherapy. Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. N Engl J Med. Sep 27 2012;367(13):1187–97. PMID:22894553. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1207506.

4. Abiraterone and Increased Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. N Engl J Med. May 26 2011;364(21):1995–2005. PMID:21612468. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1014618.

5. The Role of Physician Specialty in the Underutilization of Standard-of-Care Treatment Intensification in Patients With Metastatic Castration-sensitive Prostate Cancer. Swami U, Hong A, El-Chaar NN, et al. J Urol. June 2023; 209(6):1120–1131. PMID:36789668. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003370.

6. Adoption of Abiraterone and Enzalutamide by Urologists. Caram MEV, Kaufman SR, Modi PK, et al. Urology. Sep 2019; 131:176–183. PMID: 31136769. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2019.05.012.

7. Adherence and Out-of-Pocket Costs among Medicare Beneficiaries who are Prescribed Oral Targeted Therapies for Advanced Prostate Cancer. Caram MEV, Oerline MK, Dusetzina S, et al. Cancer. Dec 1 2020;126(23):5050–5059. PMID:32926427. doi:10.1002/cncr.33176.

8. The Impact of Health Insurance on Cancer Care in Disadvantaged Communities. Abdelsattar ZM, Hendren S, Wong SL. Cancer. Apr 1 2017;123(7):1219–1227. doi:10.1002/cncr.30431.

9. Veterans Health Care Act of 1992, Public Law 102–585. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed May 27, 2023. https://www.va.gov/opal/nac/fss/publicLaw.asp# :~:text=Public%20Law%20(PL)%20102%2D, receiving%20payment%20from%20certain %20entities

10. 340B Drug Pricing Program. Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://www.hrsa.gov/opa.

11. A Comparison of Medication Access Services at 340B and non-340B Hospitals. Rana I, von Oehsen W, Nabulsi NA, et al. Res Social Adm Pharm. Nov 2021;17(11):1887–1892. PMID:33846100. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.03.010.

12. Drug Discount Program: Federal Oversight of Compliance at 340B Contract Pharmacies Needs Improvement. Accessed May 27, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-480.

13. Consequences of the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Desai SM, McWilliams JM. N Engl J Med. Feb 8 2018;378(6):539–548. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1706475.

14. 340B Drug Pricing Program and Hospital Provision of Uncompensated Care. Desai SM, McWilliams JM. Am J Manag Care. Oct 2021;27(10):432–437. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2021.88761.

15. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, et al. N Engl J Med. Jul 27 2017;377(4):352–360. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1704174.

16. Enzalutamide with Standard First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, et al. N Engl J Med. Jul 11 2019;381(2):121–131. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903835.

17. Prostate Cancer Version 4.2023. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/ physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf.

Team Members

Kassem Faraj, MD1; Samuel R Kaufman1; Mary Oerline1; Lindsey Herrel, MD, MS1,2, 3; Megan E V Caram, MD2,3,4,5; Vahakn Shahinian, MD, MS2,3,5; Brent K Hollenbeck, MD, MS1

Affiliations: 1Department of Urology, Medical School, University of Michigan; 2Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, University of Michigan; 3Rogel Cancer Center, University of Michigan; 4Center for Clinical Management Research, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System; 5Department of Internal Medicine, Medical School, University of Michigan.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Please contact Eileen Kostanecki, IHPI’s Director of Policy Engagement & External Relations, at [email protected] or 202-554-0578.